"No Chains, No Surrender: The Blazing Courage of Prafulla Chaki"

“মরিতে চাহি না আমি সুন্দর ভুবনে,

মানবের মাঝে আমি বাঁচিবারে চাই।”

— চরন কবি মুকুন্দদাস

(“I do not wish to die in this beautiful world;

I wish to live on—among the people.”)

Yet some lives blaze so brightly that death cannot extinguish them.

Prafulla Chaki was just 19 when he laid down his life, not in search of glory, but out of unwavering devotion to India’s liberation. In an age when the very word "freedom" was enough to land a youth in the gallows, Prafulla walked the path of armed resistance, shoulder to shoulder with names like Khudiram Bose.

From his early days in the revolutionary network of Jugantar to his final act of defiance — taking his own life to avoid capture — Chaki’s story is not just one of martyrdom, but of unyielding courage, of a boy who chose death over betrayal.

This blog post revisits the life, ideals, and silent heroism of a young man who lived—and died—not to be remembered, but to awaken a nation.

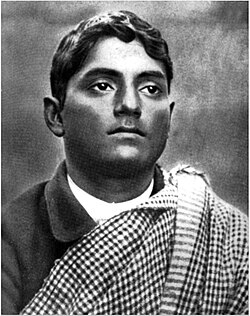

Prafulla Chandra Chaki

| Born | December 10, 1888 Bogra, Bengal Presidency, British India |

| Died | May 2, 1908 (aged 19) Mokama Ghat, Bihar, British India |

| Other names | Phulu, Dinesh Chandra Ray |

| Alma mater | Rangpur Zilla School (discontinued) |

| Occupation | Revolutionary |

| Organization | Jugantar |

| Known for | Attempt to assassinate Magistrate Kingsford at Muzaffarpur, failed escape and death |

| Movement | Indian independence movement |

Prafulla Chandra Chaki (10 December 1888 – 2 May 1908) was a fearless patriot and a determined revolutionary in India’s freedom struggle, remembered for his unwavering resolve and sacrifice in the face of colonial tyranny. Associated with the Jugantar group, Chaki rose to prominence through his involvement in the attempted assassination of British magistrate Douglas Kingsford, alongside the youthful martyr Khudiram Bose. Born in Bogra (now in Bangladesh) into a middle-class Jotedar family, Chaki was expelled from Rangpur Zilla School for participating in a student protest against British authority. He later joined Rangpur National School, where he came into contact with revolutionary ideas and nationalist thinkers.

Recognizing his zeal and courage, Barindra Kumar Ghosh brought him to Calcutta, where Chaki became an active member of the revolutionary underground. He was entrusted with several high-risk missions, including planned attacks on British officials such as Sir Bampfylde Fuller and Sir Andrew Fraser, both notorious for their role in suppressing nationalist activities.

Chaki's most audacious assignment was the assassination of Kingsford, infamous for his brutal judgments against political activists. On 30 April 1908, Chaki and Bose targeted a carriage they believed carried Kingsford, but the bomb they hurled tragically claimed the lives of two British women instead. As they fled in separate directions, Chaki was recognized by Sub-Inspector Nandalal Banerjee at Mokama Station. Refusing to surrender to the British, Chaki chose martyrdom and ended his life with his revolver. His severed head was later sent to Calcutta for identification by the arrested Khudiram.

The betrayal by Nandalal Banerjee did not go unpunished—he was later assassinated by Indian nationalists in retribution. While Mahatma Gandhi disapproved of such violent methods, Bal Gangadhar Tilak strongly defended Chaki and Bose, leading to his own arrest and intensifying the national debate on revolutionary action.

The legacy of Prafulla Chaki shines as a beacon in the saga of India’s struggle for independence—a fearless youth who chose martyrdom over surrender. His daring spirit ignited the fires of resistance in the hearts of countless patriots, making him an enduring symbol of youthful defiance against colonial oppression. Let us now delve deeper into the life and revolutionary path of this forgotten son of Bharat—unfolding stories and sacrifices that remain unknown and unheard by many.

Early life and family background

Prafulla Chandra Chaki was born on 10 December 1888 (27 Ogrohayon 1295 B.S.) in the serene village of Bihar, also known as Vasu Vihara, nestled in the Bogra district of present-day Bangladesh—then a part of the Bengal Presidency under the iron grip of British colonial rule. He came from a lineage steeped in dignity and self-respect. His great-grandfather, Prankrishna Narayan Chaki, hailed from the Kayastha community and resided in Chanchakiya, a village in the Pabna district. Prankrishna's son, Mahendranarayan Chaki, later relocated to Madla village in Bogra, laying down the roots of a family that would one day give birth to a fearless patriot.

Of Mahendranarayan’s three sons—Indranarayan, Lakshminarayan, and Chandranarayan—it was Chandranarayan, the youngest, who shifted to Vasubihar and firmly established the family there. Chandranarayan stood apart for his fierce independence. In an era when most leaned on extended kin, he chose the path of self-reliance, earning his livelihood through honest labor. This proud defiance of dependency forged a lasting legacy of discipline, resilience, and integrity in the family.

His son, Rajnarayan Chaki, carried forward this legacy, working in the Nagar estate. Rajnarayan married twice—his first wife passed away childless, and his second marriage to Swarnamoyee Devi brought forth a large family. They were blessed with four sons—Pratapchandra, Jagatnarayan, Charuchandra, and the youngest, Prafulla Chandra Chaki—as well as two daughters, Kusumkamini and Saudamini. The Chaki household earned wide respect in the locality for their grace, hospitality, and deep-rooted spiritual values.

Childhood and education

As the youngest of four brothers, Prafulla Chandra Chaki spent his early years in the warmth of a family that, for a time, enjoyed modest prosperity. Being the youngest, he was enveloped in affection, and his formative days were shaped by the nurturing presence of his mother, Swarnamoyee Devi—a woman of gentle temperament and deep empathy, who hailed from a respected family in Bogra.

Tragedy struck early in Prafulla’s life. In 1298 B.S., when he was just three years old, his father, Rajnarayan Chaki, succumbed to a contagious disease. The loss cast a long shadow over the household, plunging the family into emotional grief and financial hardship. It was Pratap Chandra Chaki, the eldest brother—barely a young man himself—who rose to the occasion. Having just completed his F.A. (First Arts) examination, Pratap took charge of the family’s responsibilities. He found employment as a Circle Officer under Abdul Shobhan Chowdhury, a local zamindar of Bogra, thereby anchoring the family during a difficult time with rare maturity and resolve.

Prafulla began his education at the age of six, initially guided by a home tutor. He was soon admitted to Namuja Bhagabandas Prasad Middle English School, where he maintained a steady academic record. Though not a standout in the classroom rankings, he was an earnest student, curious and diligent. What set him apart was his early thirst for knowledge, often venturing beyond textbooks to read independently—a spark that hinted at the bold thinker he would become.

At the age of fourteen, having completed his primary schooling, Prafulla was sent to Rangpur to pursue further education. There, he stayed with Pratap Chaki, whose father-in-law was a prominent citizen of the town. In Rangpur, Prafulla enrolled at the Rangpur Zilla School, an institution that would silently witness the early stirrings of his awakening as a revolutionary mind.

Political awakening and Swadeshi activism

Partition agitation and student protest (1905–1906)

The Partition of Bengal, officially proclaimed on 1 September 1905 and implemented on 16 October 1905, sent shockwaves through Bengal, igniting a wildfire of nationalist awakening. What the colonial rulers intended as a mere administrative division was swiftly recognized by the people as a calculated attempt to fracture Bengal’s cultural and political unity. In response, a powerful wave of public resistance surged across the province, giving birth to the Swadeshi Movement—a call to reclaim self-respect through self-reliance.

On the day the partition came into force, 16 October, thousands observed "Rakhi-bandhan Day", a symbolic gesture of fraternal unity and defiance. People tied sacred threads on each other’s wrists, reaffirming their bond as sons and daughters of the same motherland. The streets echoed with Vande Mataram, and protest fasts and barefoot marches became the chosen weapons of the youth.

The British colonial authorities, alarmed by the spirit of unity and the political awakening among students, reacted with oppressive urgency. In a show of brutal discipline, pupils from Dhaka Collegiate School and Rangpur Zilla School, who took part in barefoot protest fasts on 17 October, were publicly caned—a deliberate attempt to humiliate and suppress. And just days later, on 22 October 1905, the notorious Carlyle Circular was issued. It formally prohibited students from engaging in any political activity, marking a dark chapter in the regime's bid to stifle young voices.

But far from extinguishing the flame, these actions only deepened the resolve of Bengal’s youth, Prafulla Chandra Chaki among them, to rise in defiance of imperial injustice.

At Rangpur Zilla School, Prafulla Chandra Chaki and several of his spirited classmates—Prafulla Chakraborty, Paresh Mallik, Narendranath Bakshi, Krishna Jiban Sanyal, and others—became early casualties of colonial repression. When the Carlyle Circular demanded written "good conduct" declarations from students, they stood firm in resistance. Refusing to bow to colonial diktats, they withdrew from the institution, choosing principle over comfort.

These brave young minds soon found sanctuary in the Rangpur National School, a pioneering effort founded by the visionary educator Nripendra Chandra Bandyopadhyay. It was the first "national" (non-aided) school in Bengal, born out of the Swadeshi spirit, free from government interference and steeped in nationalist ideals. Within its walls, a new generation of patriots was being forged.

At this turning point in Prafulla’s life, he encountered Brajasundar Rai, a dedicated teacher at the National School. It was Rai who first ignited the spark of nationalism in young Chaki—a spark that would later be fanned into flames under the towering influence of Barindra Kumar Ghosh, a key architect of Bengal’s revolutionary underground.

Here, Prafulla immersed himself in the life-changing philosophies of Swami Vivekananda, the call to duty and fearlessness in the Bhagavad Gītā, and the whispered pages of secret revolutionary pamphlets. He also joined the Bandhav Samiti, a local physical-culture club that doubled as a nationalist study circle—where the body was strengthened and the soul steeled for the sacred struggle of liberation.

Contact with Jugantar and early operations (1906–1907)

In late 1906, Barindra Kumar Ghosh, the fiery architect of the Jugantar revolutionary group, toured North Bengal in search of young men with both physical strength and unshakable will—the kind of youth who would fearlessly commit themselves to the armed struggle for India’s liberation. Among those who stood out was Prafulla Chandra Chaki. His robust physique and unwavering resolve made an immediate impression on Barin Ghosh, who welcomed him into the inner circle of Jugantar. Soon after, Chaki was summoned to Calcutta to join operations at the secret Maniktala Garden bomb factory, established in 1907, where the alchemy of revolution was underway.

Before leaving Rangpur, Chaki had already thrown himself into several covert nationalist activities that revealed both his boldness and strategic mind:

-

Anti-Circular Society: With his fellow students, Chaki distributed handbills denouncing the Carlyle Circular, rallying public opposition. They also organized pickets outside government-aided schools, urging students to reject colonial education in favor of national self-respect.

-

Attempted “Swadeshi Dacoity” (1906): In a daring move near Rangpur, roughly 12 miles from the town, Chaki joined Barin Ghosh in a fund-raising raid aimed at collecting money for revolutionary work. Though the operation did not succeed, it was recorded in police files as Bengal’s first planned political burglary, marking a bold new phase in revolutionary strategy.

-

Mission to Nepal (1906–1907): Travelling under the collective pseudonym “Panch Pandav,” Chaki, along with Upendranath Bandhopadhyay, Ullaskar Dutta, Satish Sarkar, and Bibhuti Bhushan Sarkar, accompanied Jnanendranath Mitra to Dhuni Sahib’s ashram in Nepal. Their goal was to secure spiritual and logistical support from monastic circles for armed resistance. Though the attempt did not yield the desired alliance, it significantly expanded Chaki’s underground contacts and regional reach.

By 1907, Prafulla Chaki had fully transitioned into the heart of the revolutionary movement in Kolkata. He immersed himself in training in bomb-making, revolver use, and secret communication techniques. As his trust and stature within Jugantar grew, he was soon chosen for a critical mission—a political assassination that would become known as the Muzaffarpur Conspiracy of 1908, a defining episode in India’s early revolutionary history.

Commitment to the revolutionary cause

Life at Maniktala and yogic discipline

In early 1907, Prafulla Chandra Chaki moved from Rangpur to Kolkata and formally joined the Jugantar group at Muraripukur, popularly known as the Maniktala Garden. There, in the nerve centre of Bengal's underground revolution, Chaki was inducted into the Central Committee, representing the Rangpur branch. He quickly developed close ties with leading revolutionaries like Barin Ghosh, Ullaskar Dutta, and Upendranath Bandhopadhyay, becoming a vital link in Jugantar’s growing network of militant youth.

At Maniktala, Chaki underwent intensive training in all aspects of revolutionary warfare—bomb-making, revolver handling, secret courier routes, and coded communication. But beyond his skill and intellect, what made him stand out was his remarkable personal discipline, both physical and spiritual. He embraced a life of self-restraint, fasting regularly and devoting himself to deep spiritual study. He would be seen immersed in the Gita, the Upanishads, and the Chandi, and had a particular devotion to Chamunda, the fierce form of the Mother Goddess.

A telling episode from this time reveals the high regard in which he was held. Aurobindo Ghosh’s spiritual mentor, Vishnu Bhaskar Lele, once visited the garden and, upon witnessing Chaki’s yogic discipline and physical prowess, was so taken with the young man that he "expressed a desire to take him along for advanced yogic training." However, this request was met with concern among Jugantar’s senior members, who believed that Chaki’s presence at the garden was essential to the movement.

When the matter was brought before Barin Ghosh, he asked Chaki directly whether he wished to accompany Lele. Prafulla replied that unless he was dismissed, he preferred to remain at the garden, dedicated to the revolutionary cause. His quiet but firm words deeply moved his comrades and further strengthened his reputation as a committed and self-sacrificing soldier of freedom.

Even while operating from Kolkata, Chaki remained deeply attached to his mother. He often made secret visits to Bagura, taking great care to avoid surveillance. In later days, he would meet her only at night to avoid detection—a poignant reminder of the personal sacrifices made by those who chose the path of revolution.

Meeting Bagha Jatin

In 1907, Prafulla Chandra Chaki was sent on a clandestine mission to Darjeeling, a hill station cloaked in mist—and now, revolutionary whispers. His task was to establish contact with Bagha Jatin, the legendary nationalist who had recently been transferred there on a special assignment from the Bengal Secretariat. Known for his affable nature and warm hospitality, Jatin had quickly transformed his residence into more than just a home; his house in Darjeeling reportedly became a hub for revolutionary discussions. Within those quiet hills, away from the eyes of the colonial police, young patriots gathered, strategy merged with inspiration, and the dream of liberation deepened its roots. It was in such electrifying company that Prafulla began preparing for the storm that lay ahead.

Prafulla Chandra Chaki arrived in Darjeeling carrying a letter of introduction from Barin Ghosh, the seal of revolutionary trust. There, in the shadow of the hills, he met the legendary Bagha Jatin, whose quiet strength and magnetic personality left a lasting impression on all who encountered him. After confirming Jatin’s identity, Prafulla revealed the true nature of his mission: he had come from the Maniktala Garden on a highly sensitive assignment—the assassination of Lieutenant Governor Sir Andrew Fraser, one of the chief architects of British administrative repression in Bengal.

Jatin welcomed him into his home with his characteristic warmth. Prafulla spent two days with Jatin’s family, observing firsthand the depth of his host’s patriotic convictions. During this time, Chaki reiterated his mission, eager to act. But Jyoti, as Jatin was affectionately known, assessed the ground reality and advised caution. The moment was not right, he explained, and assured Prafulla that "he would be called when the opportunity presented itself."

Back in Calcutta, Prafulla often spoke with admiration of Bagha Jatin, praising his character, composure, and revolutionary zeal. But this admiration did not sit well with Barin Ghosh, who harbored doubts about Jatin’s position within the government service. One day, visibly irritated, Barin confronted Prafulla. "I sent you to Darjeeling to test his patriotism. He's a government employee—do you really think he will liberate India?" The remark stung like a blow. For someone like Chaki, whose sense of loyalty and instinct for character were rooted in deep sincerity, such suspicion was unbearable.

Deeply wounded, he fell silent. Consumed by inner turmoil, he refused food and water for several days, retreating into himself as a quiet act of protest and pain.

In time, the ripple effect of his words became evident. Another young revolutionary, Phani Chakraborty, arrived in Darjeeling, sent from Kolkata. Though discreet about his own assignment, he made it known that he had come inspired by Prafulla’s unwavering faith in Jatin, a silent testament to how deeply Chaki’s spirit and conviction had begun to influence the ranks of Bengal’s rising revolutionaries.

Attempt to assassinate Sir Bamfylde Fuller

In 1907, Prafulla Chandra Chaki took part in what is now regarded as one of the earliest organised assassination attempts against a British colonial official in Bengal—the plot to eliminate Lieutenant Governor Sir Bampfylde Fuller. Conceived by senior members of the Jugantar group, including Barin Ghosh, this bold plan reflected the rising tide of radical nationalism that swept across Bengal in the wake of the Partition. The revolutionaries had grown convinced that only direct action could answer the increasing brutality of British repression.

With financial support secured, Barin Ghosh himself travelled to Shillong, the summer capital of Eastern Bengal and Assam, carrying with him firearms and primitive explosives. The original plan was to make final arrangements in Shillong and summon Hemchandra Kanungo from Midnapore for the execution. But as complications mounted, the operation was repeatedly shifted—first to Guwahati, then Barisal, and eventually to Rangpur. Each location presented fresh challenges: unreliable networks, lack of local infrastructure, and Fuller’s constantly changing travel itinerary.

It was during this phase that Prafulla Chaki was recruited in Rangpur to assist directly in the mission. Already known for his discipline, courage, and complete dedication, he quickly emerged as one of the most trusted hands in the operation. When intelligence indicated that Fuller would pass through Naihati Junction, Chaki and Hemchandra sprang into action. They arrived at the station, armed and ready, determined to board the lieutenant governor’s train and carry out the assassination inside his compartment.

But fate took another turn. Fuller’s train was rerouted unexpectedly, bypassing Naihati altogether. The carefully laid plan collapsed. For Chaki and Hemchandra, the failure brought bitter disappointment, but not defeat. They returned to Calcutta and reported to Sri Aurobindo, who listened with quiet resolve and encouraged them to continue undeterred in the revolutionary path.

Though the mission did not succeed, it marked a decisive shift in the revolutionary movement. This was the first recorded attempt at political assassination in modern Bengal—a bold precedent that would inspire a generation of young patriots. For Prafulla Chaki, it was a defining moment. His willingness to face death and the calm precision with which he executed orders earned him the full confidence of senior Jugantar leaders and deepened his role in the underground struggle for freedom.

Attempt to assassinate Sir Andrew Fraser

Darjeeling and Mankundu plots (1907)

In late 1907, Sir Andrew Fraser, the much-reviled Lieutenant-Governor of Bengal, arrived in Darjeeling for the Puja holidays. For Bengal’s revolutionaries, his presence was an opportunity not to be missed. Charu Chandra Dutt, a revolutionary sympathiser then posted in Darjeeling as a government officer, saw a chance to strike a decisive blow. Without delay, he summoned Prafulla Chaki from Kolkata to carry out the bold task.

The first plan was simple but daring. Fraser typically walked to church on Sundays, unguarded. Prafulla, armed with a bomb smuggled from Calcutta, would position himself along the path, while Dutt waited at the nearby railway platform to assist in the escape. But fate intervened. On the appointed day, Fraser was unexpectedly accompanied by a police escort, making any action impossible. The conspirators held back, determined not to act rashly. A second chance came during a public cricket match, but once again, Fraser failed to appear, and the mission had to be abandoned.

Unshaken, the revolutionaries soon devised another plan: to assassinate Fraser on his return journey from Darjeeling. This time, the chosen strike point was Mankundu, near Chandannagar. Ullaskar Dutta crafted a formidable iron bomb, packed with dynamite and fitted with picric acid-based detonators. Alongside Barin Ghosh and other team members, Prafulla Chaki participated in the groundwork, helping scout the area and organize logistics. The team dug a shallow trench to lay an explosive charge beneath the railway tracks.

But as they worked under cover of night, passers-by disturbed their operation, and unexpected complications emerged. In a split-second decision, Ullaskar threw a few sticks of dynamite onto the tracks in hopes of causing damage, but the explosion proved ineffective, and Fraser’s train passed unharmed.

Still undeterred, the group made a second attempt days later. This time, Prafulla Chaki, Bibhuti Bhushan Sarkar, and Barin Ghosh returned to Mankundu, selecting a position near a railway bridge. They waited patiently through the night, mine set and nerves steeled. But once again, the mission was foiled—the train never arrived.

Narayangarh bombing attempt (1907–1908)

Buoyed by a steady flow of funds and inspired by the unwavering dedication of young patriots like Prafulla Chaki, the Jugantar group prepared for a more ambitious and carefully orchestrated attempt to assassinate Sir Andrew Fraser. The new opportunity emerged in December 1907, when Fraser was scheduled to return from a tour of famine-struck Orissa. His route would pass through Narayangarh, a remote and desolate location near Kharagpur, adjacent to Midnapore—a hotbed of revolutionary activity under Satyendranath Bosu, a key figure in Aurobindo Ghosh’s network.

Once again, Ullaskar Dutta was entrusted with preparing the explosive—a powerful mine packed with six pounds of dynamite, encased in an iron vessel and fitted with picric acid-based detonators and a fuse made from the same compound. Prafulla Chaki and Bibhuti Bhushan Sarkar formed the advance team. They travelled to Narayangarh, scouted the area, and dug a pit to conceal the mine beneath the tracks. After completing the groundwork, they returned to Calcutta to await final confirmation of Fraser’s train schedule.

On 5 December 1907, Prafulla, Barin Ghosh, and Bibhuti Bhushan made their way back to Narayangarh. Under Barin’s direction, Chaki and Bibhuti carefully set the mine. After the groundwork was completed around midnight, Barin departed for Calcutta, and once his train had passed, the two revolutionaries inserted the fuse and withdrew under the cover of darkness.

Their retreat was grueling. According to Bibhuti Bhushan Sarkar, thirty-two thorns were pulled from Prafulla Chaki’s feet after the team had to traverse dense forest in their escape, evading capture through sheer endurance and stealth.

In the early hours of 6 December, Fraser’s train rolled over the mine. A tremendous explosion shattered the silence—rails were twisted, several sleepers splintered, and a crater five feet deep marked the blast site. The locomotive was violently lifted, but miraculously, the train did not derail, and Fraser escaped unharmed.

The British authorities responded swiftly, launching an intensive investigation. A group of innocent coolies were arrested based on coerced testimony and convicted in 1908, though they were eventually acquitted and released in 1910 when the charges were proven fabricated. Meanwhile, the Criminal Investigation Department (CID) became convinced that the explosion was the handiwork of a growing and highly organised anarchist network.

Though the primary objective—to eliminate Fraser—was not achieved, the Narayangarh operation marked a turning point. It was one of the most technically advanced assassination attempts in colonial India up to that time. The operation demonstrated the revolutionaries’ growing proficiency in explosives and guerrilla tactics, and it cemented Prafulla Chaki’s reputation as a fearless and dependable operative. His cool execution, physical stamina, and quiet resolve earned him a permanent place in Barin Ghosh’s inner circle, as one of the movement’s most trusted and dedicated soldiers of the revolution.

Plan to assassinate Kingsford

Background and decision

By mid-1907, Douglas Hollingshed Kingsford, the Chief Magistrate of Calcutta Presidency, had become a symbol of colonial tyranny in the eyes of Bengal’s revolutionaries. Known for delivering harsh sentences in sedition cases and infamous for ordering the public flogging of a young boy, Sushil Sen, Kingsford’s name became synonymous with brutal injustice under British rule. Within nationalist circles, it was no longer a question of whether to eliminate him—but how.

One of the earliest assassination attempts against Kingsford was a remarkable act of ingenuity and daring. Revolutionaries prepared a bomb hidden inside a hollowed-out book—a 1,200-page volume meticulously carved to conceal a tin case filled with picric acid, a spring-loaded trigger, and a fulminate of mercury detonator. When the string binding the book was cut, the cover would snap open, triggering the deadly charge. The delivery was carried out by Paresh Mallik, posing as a chaprasi (office orderly). The book reached Kingsford’s residence at Garden Reach in Calcutta and was mistakenly shelved unopened as a returned volume. Though the device did not explode, a later British investigation revealed the rusted mechanism still intact—a bomb that had nearly altered history.

Before the revolutionaries could attempt another strike, Kingsford was transferred by the colonial government to Muzaffarpur, Bihar—a move made largely for his protection. But distance could not shield him from the fire that had already been lit.

Within a week of his relocation in March 1908, Barin Ghosh, with the tacit approval of Sri Aurobindo, Subodh Mallik, and Charu Chandra Dutt, formulated a new plan to eliminate the magistrate. Though later accounts would dramatize it as a “revolutionary tribunal’s death sentence,” contemporary sources suggest it was more likely a collective, informal consensus, strongly driven by Barin’s resolve.

The decision was clear: Kingsford must fall, and in doing so, shake the foundations of imperial arrogance.

Selection of operatives: Prafulla and Sushil

For a mission as perilous as the assassination of Kingsford, Barin Ghosh initially selected a young revolutionary whose very body bore the scars of colonial brutality—Sushil Sen, the same youth who had once been publicly whipped on Kingsford’s orders. The symbolism was potent. His motive was unmistakable, and if captured, it was believed that his personal vendetta might shield the larger revolutionary network from exposure. But though Sushil’s passion burned brightly, his inexperience made him a risk for a mission of such gravity.

Barin needed someone with calm nerves, battle-tested discipline, and unflinching resolve. He turned to none other than Prafulla Chandra Chaki.

Only nineteen years old, Prafulla had already carved out a name for himself in Bengal’s revolutionary underground. From a quiet schoolboy in Rangpur, he had transformed into a master of covert operations, well-versed in explosives, sabotage, and secret communications. At the Muraripukur Garden, comrades spoke of his unyielding focus and steely composure. He was known for his refusal to be taken alive. In fact, he had once put an empty pistol in his mouth, demonstrating his plan to evade capture if cornered. He had said plainly:

"This is the only sure way. Any other way, and most of the time you just wound yourself."

It was this unshakeable spirit that convinced Barin. Prafulla would not fail. And even in failure, he would never betray.

Thus, the two young revolutionaries—Sushil Sen, burning with righteous rage, and Prafulla Chaki, cold and prepared—were paired for the mission to assassinate Kingsford in Muzaffarpur. It would become one of the most fateful operations in the annals of India’s revolutionary struggle.

Preparation and reconnaissance in Muzaffarpur

Around 4 April 1908, Prafulla Chandra Chaki and Sushil Sen set off from Calcutta toward Muzaffarpur, carrying not just weapons and aliases, but the solemn weight of a historic mission. Traveling under the assumed names Dinesh Chandra Roy (for Prafulla) and Durgadas Sen (for Sushil), the two young revolutionaries blended into the crowd, determined to bring justice to the man who had become a hated symbol of British repression—Douglas Kingsford.

Upon arrival in Muzaffarpur, they took shelter in a dharamshala managed by Kishori Mohan Banerjee, a fellow Bengali. But trouble arose quickly. Sushil accidentally misplaced a significant portion of their operational funds, jeopardizing the mission. Calm and composed under pressure, Prafulla wrote back to the Garden (Muraripukur) for help. This handwritten note would later resurface as crucial evidence in the Alipore Bomb Case.

Penned under his alias, the letter read:

"Dear Suku da (Barin Ghosh), We have safely reached here. All the money in Durgadas's pocket was lost on the way. Because of this, we are in great trouble. Please send 20 rupees to the address below."

In a code known only to his comrades, he added with subtle irony:

"We have not seen the bridegroom yet."

—a chilling reference to Kingsford, the intended target.

Ever cautious, Prafulla advised that the money be sent using a false return address, a small but telling example of the methodical secrecy that defined these underground operatives.

Their plea did not go unanswered. On 9 April, ₹20 arrived via money order, sent by Barin Ghosh—a lifeline that allowed the mission to continue. Over the next few days, Prafulla and Sushil conducted quiet surveillance around Kingsford’s residence. They studied his movements, marked timings, assessed escape routes, and noted changes in security. Every detail was logged with military precision.

Having gathered the necessary intelligence, they briefly returned to Calcutta to meet with the leadership. It was now time to finalize the plan—and deliver the blow that would shake the empire.

Selection of the assassins and CID surveillance

Prafulla Chaki and the final choice of assassins

Following their second reconnaissance trip to Muzaffarpur, Prafulla Chaki and Sushil Sen returned to Calcutta to make the final preparations for executing Judge Douglas Kingsford. The target was clear, the plan was in motion—but fate introduced an unexpected turn. Sushil received word that his father lay critically ill in Sylhet. Torn between the call of revolution and familial duty, Sushil faced a painful decision. In the end, he chose to be by his father's side, stepping away from a mission that had already become historic in its scale and risk.

With Sushil's departure, the revolutionary leadership had to act swiftly. On the recommendation of Hemchandra Kanungo, a new name was proposed: Khudiram Bose. Barely eighteen years old, Khudiram was already a seasoned participant in the freedom struggle. Since 1905, he had stood at the frontlines of boycott movements, seditious protests, and nationalist processions. Young in years but bold in spirit, Khudiram’s commitment to the cause was unquestionable. Yet even with his growing reputation, Prafulla remained the senior commander of the operation.

In late April 1908, Barin Ghosh took Prafulla to Gopi Mohan Dutt's Lane, where they retrieved the bomb constructed by Hemchandra and Ullaskar Dutta. It was a spherical tin device, carefully packed with six ounces of dynamite, a detonator, and a black-powder fuse—deadly, compact, and designed for a precise strike.

The next stop was Hem’s residence on Raja Naba Krishna Street, where Prafulla was formally introduced to Khudiram—but only by his alias, Dinesh Chandra Roy. In a telling example of revolutionary secrecy, the two never exchanged their real names, even as they prepared to carry out a mission that could cost them their lives.

With three revolvers and the bomb concealed in a Gladstone bag, the two revolutionaries boarded a train to Muzaffarpur. Upon arrival, they checked into the dharmsala of Kishori Mohan Banerjee—the same safe house used in earlier surveillance missions. Every detail was set. The plan was in motion. The hour of reckoning had arrived.

Leak of the plot and CID countermeasures

Unknown to Prafulla Chaki and his comrades, the veil of secrecy surrounding the Kingsford mission had been pierced. Around mid-April 1908, a fateful breach occurred. Abinash Bhattacharya, a trusted associate of both Barin Ghosh and Sri Aurobindo, casually divulged crucial details of the assassination plan to an acquaintance named Rajani Sarkar—unaware that Rajani was an informant working for the Criminal Investigation Department (CID).

The consequences were immediate. Rajani reported the conversation to his handler, Deputy Superintendent Ramsaday Mukherjee, who in turn relayed the intelligence to Police Commissioner F. L. Halliday on 20 April 1908. The message was brief but ominous: two unidentified Bengali youths had departed for Muzaffarpur with the intent to assassinate Kingsford.

Though the tip lacked specifics, Halliday did not take it lightly. He urgently notified J. E. Armstrong, the Superintendent of Police in Muzaffarpur, instructing him to remain vigilant. Kingsford, arrogantly dismissive of the danger, refused to alter his habits—but Armstrong was not so complacent. He posted plainclothes constables near Kingsford’s residence and along his evening route to the Muzaffarpur European Club—the judge’s only predictable public outing.

On the night of 29 April, CID officers spotted two young men lingering near the maidan opposite the Club. They were approached and questioned. The pair replied in uncertain, broken Hindi, claiming to be students staying at a nearby dharmsala. The officers let them go, failing to grasp the danger that stood before them.

But the storm was about to break.

Final visit and family farewell

Before embarking on the fateful Muzaffarpur mission, Prafulla Chaki returned home to Bagura one final time, in late February 1908. It was not just a visit—it was a farewell cloaked in silence, a final act of devotion to his family and his inner calling. During this stay, he received spiritual initiation from the family guru, solidifying his resolve and embracing a life of renunciation and martyrdom.

He also spent time with his mother and siblings—each interaction laden with unspoken meaning. One day, his younger sister Saudamini, unaware of what was to come, innocently asked her beloved brother:

“Chhorda, won't you get married?”

In response, Prafulla quietly lifted his shirt to reveal a scar on his chest—a mark from his revolutionary training—and answered with calm finality:

“As long as this mark remains, I cannot settle into family life.”

It was a moment that would stay etched in the hearts of those he left behind.

His elder brother, Pratap Chaki, sensing the depth of Prafulla’s resolve, pleaded with him to remain home and offered him his share of the family property. But Prafulla, already inwardly detached from worldly attachments, replied:

“My share will go to Ma. After that, you all can divide it among yourselves.”

These words were more than a farewell—they were a testament to his self-sacrifice, his devotion to the motherland, and his readiness to walk the lonely road of revolution. Prafulla Chaki left home not merely as a son, but as a soldier of India’s awakening.

Staying at Muzaffarpur

In the afternoon of 1908, after bidding farewell to their comrades at Muraripukur Garden, Prafulla Chaki and Khudiram Bose set out on their fateful journey to Muzaffarpur—a distance of nearly 375 miles (604 km) from Calcutta. They carried with them a bomb, revolvers, and above all, the unshakable resolve to strike a blow against the British Raj.

Upon arrival at dusk, the two young revolutionaries took shelter at a dharamshala located at the city’s entrance, owned by a local zamindar, Parameshwar Mahato. It would be their temporary base for observation and preparation.

The very next morning, Prafulla and Khudiram set out to survey the town. Their eyes were fixed on one place alone—the residence of Judge Kingsford. They observed his bungalow with care, noting movements, timings, and security arrangements. Later, they drew a detailed hand-map, clearly marking both the judge’s home and their own lodging. This hand-drawn map would later be discovered during the police raid on Muraripukur Garden, offering evidence of the operation’s meticulous planning.

To support their stay, Prafulla arranged for ₹202 to be sent from Calcutta by money order, addressed to Kishori Mohan Bandyopadhyay, head clerk of the Ward Estate, whose office was conveniently situated inside the dharamshala. Meanwhile, another coded letter was dispatched to Barindra Kumar Ghosh (Suku Da). Light-hearted on the surface, its subtext was grave:

"Suku da, I haven't seen the groom, but I have seen his house. Unfortunately, good rasgullas are not available here. Don't forget to send some good rasgullas. —Dinesh"

The court would later interpret “the groom” as a thinly veiled reference to Kingsford himself, while the “rasgullas” were understood as a coded request for further supplies—perhaps more bombs or equipment.

The money order arrived on 9 April. As Prafulla was away at the time, Kishori Babu signed for the funds and later handed over the amount to him upon receiving a receipt. The next morning, 10 April, Prafulla and Khudiram vacated the dharamshala.

Yet the struggle of exile was not limited to danger alone—the local food proved difficult for them to tolerate. Seeing their discomfort, Kishori Babu took pity and brought them into his own home, feeding them generously for several days. His house was located in the Siuhar Chauni area of Kazi Mohammadpur. Eventually, the two separated lodgings—Khudiram remained at the dharamshala, while Prafulla shifted to a Bengali mess in Sarairanjan, seeking to maintain their cover and expand surveillance.

Their reconnaissance work continued. They studied city streets and kept a close watch on Kingsford’s daily habits, particularly his routines to and from the European Club. Once, during a visit to the Muzaffarpur court, they aborted a planned attack to avoid civilian casualties, a decision that speaks volumes of their moral discipline—even as they prepared for violent resistance.

Meanwhile, tension was rising. A threatening letter was sent to Kingsford, prompting authorities to assign two constables, Tahsildar Khan and Faizuddin, to guard his residence and tail him during his public movements.

The noose was tightening. The stage was nearly set.

Futile assassination of Kingsford

On 29 April 1908, Prafulla Chaki and Khudiram Bose once again surveyed the area near Kingsford’s bungalow, their eyes sharp, their movements discreet. As they observed the judge’s routines around the racquet court, they happened upon a group of local boys and met a student named Abdul Karim, who invited them to join a football match. Prafulla, agile and composed even under pressure, played with remarkable skill and helped secure a 3–0 victory. The boys cheered the mysterious young man, asking where he was from. Calmly, they replied that they were visitors from Naihati—a cover story prepared long in advance.

That evening brought no opportunity to strike. With time running out, they made a solemn decision: if no chance emerged by the following afternoon, they would carry out the assassination as Kingsford returned from the European Club, where he played bridge most nights, usually heading home around 8 PM in a horse-drawn landaulet. As fate would have it, 30 April was Amavasya, the new moon night—a symbolically potent moment in Indian tradition, and an ideal time for shadowed vengeance.

The morning of Thursday, 30 April, passed without event. But by 7 PM, Prafulla and Khudiram had taken up separate positions near Kingsford’s bungalow. At 7:30 PM, constables Faizuddin and Tahsildar Khan, stationed outside, questioned the two strangers. Speaking in halting Hindi, they explained they were “students staying nearby waiting for a friend.” The constables told them to step aside, as the road was reserved for sahibs. The young revolutionaries obeyed, but remained in position—watchful, alert, and ready.

Soon, Khudiram relayed critical news to Prafulla: Kingsford had left for the Club. But the risks were mounting. Their faces had become familiar in town. Children had begun to recognize them. It was now or never.

Khudiram carefully took out the bomb from the tin box. Together, the two moved toward the European Club, where they discreetly observed Kingsford engaged in his nightly bridge game. Prafulla briefly returned to the dharmshala, while Khudiram maintained surveillance—ever vigilant.

Later that night, under cover of darkness, they both returned and positioned themselves behind a tree near the eastern gate of Kingsford’s residence. Every detail of the plan had been etched into their minds: if the bomb failed, the revolvers would finish the job. Silently, they removed their shoes, moving barefoot through the dust—Khudiram carrying the bomb and two pistols, Prafulla with one revolver.

At 8:30 PM, the distant clatter of a carriage reached their ears. But fate had intervened. Mrs. Louie Ella Kennedy and her daughter Grace Ella Kennedy, having just left a dinner with Kingsford, had boarded a carriage nearly identical to his.

As the landaulet passed before them, Khudiram—though some say it may have been Prafulla—hurled the bomb with precision.

"The bomb's deafening explosion shook the entire city. The carriage burst into flames, and the coachman, injured, fell unconscious on the ground."

Believing they had struck their target, Prafulla and Khudiram fled into the night, back toward the dharmshala and freedom.

Meanwhile, Mr. Wilson, a British officer lodged nearby, rushed to the flaming wreck. Constable Tahsildar Khan sprinted to the station to report the bombing. A reward of ₹5,000 was swiftly announced, and urgent telegrams were dispatched to all railway junctions, tightening the net.

Unbeknownst to the attackers, their mission had gone tragically awry. Kingsford was still at the Club.

The victims in the carriage were not colonial officials, but innocents—Louie and Grace Kennedy. Both suffered horrific injuries. The coachman, too, was badly wounded. In the hours that followed:

"Miss Kennedy died within a few minutes of the explosion, and Mrs. Kennedy a little later."

The deaths of two Englishwomen shocked the British Raj to its core, unleashing a storm of repression. But for the revolutionaries, this tragic twist could not erase the intent nor the courage of those who had dared to strike at the very heart of imperial injustice.

Aftermath and police surveillance

In the moments following the explosion, Prafulla Chaki and Khudiram Bose fled swiftly from the scene of fire and chaos. At first, they headed back toward their lodging at the dharamshala, but instinct—and experience—warned them that police surveillance was likely already tightening around the city. Without exchanging words, they made a critical decision: to separate and escape in opposite directions. It was a move of survival, not fear—a strategy born of years of revolutionary discipline.

Back at the site of the bombing, Superintendent of Police J.E. Armstrong arrived with armed constables and immediately cordoned off Kingsford’s residence. Recognizing the gravity of the attack, Armstrong moved with military precision. He deployed officers to key railway stations across Bihar—Ramdhar Sharma to Bankipore, others to Mokameh and Waini—with strict orders: arrest all suspicious individuals.

To escalate the manhunt, a reward of ₹5,000 was publicly declared for the capture of the assailants. The proclamation was read aloud in marketplaces and train platforms, accompanied by the beat of drums—a colonial performance of fear and vengeance.

Disguised CID officers were embedded on outbound trains to intercept any fleeing revolutionaries. Among them were Shivprasad Mishra and Fateh Singh, posted strategically at Waini Station—a critical junction 24 miles east of Muzaffarpur, now immortalized as Khudiram Bose Pusa railway station.

Simultaneously, Armstrong ordered the search of every home owned or rented by non-local Bengalis in Muzaffarpur. The crackdown was swift and brutal. Panic swept through the city. Ordinary citizens were interrogated, letters confiscated, and books seized. But this was not merely a local operation—it signaled the beginning of a sweeping colonial backlash across Bengal and Bihar, a desperate act of suppression aimed at extinguishing the flame lit by young patriots.

And then, just a day later, on 1 May 1908, a breakthrough:

A telegram from Waini Station arrived at Armstrong’s desk. Khudiram Bose had been captured. Two officers—Mishra and Singh—had detained a lone youth, barefoot, disheveled, dust-covered, and carrying nothing but a railway timetable, a few rupees, and two revolvers.

One half of the daring duo had been taken. The hunt for the other—Prafulla Chaki—was now underway.

Manhunt and death

On foot and with blistered feet, Prafulla Chaki pressed onward from Muzaffarpur, his heart steady, his mission unfinished. He reached Samastipur, exhausted yet undeterred. There, fate brought him to Triguna Charan Ghosh, a fellow Bengali and a railway employee with the Bengal and North Western Railway.

Though aware of the widespread manhunt, Triguna Babu recognized the weariness in the young man's eyes and the quiet fire in his soul. In a moment of extraordinary moral courage, he took Prafulla in, offering food, fresh clothes, and crucially, a train ticket to Mokama Ghat. He didn’t stop there—he personally escorted Prafulla to the station, knowing full well that he was risking his job, his freedom, perhaps even his life.

Such quiet acts of solidarity were the unsung lifeblood of India’s revolution—a silent network of brave hearts who aided freedom fighters, not for glory, but for dharma.

Onboard the train, destiny once again tested Prafulla’s resolve. In the compartment were two other Bengali travelers—Mrityunjay Chakraborty, a visibly ill man returning to Kolkata, and Nandalal Bannerjee, a sub-inspector of police, and nephew of Shib Chandra Chatterjee, the government pleader of Muzaffarpur.

Bannerjee, already alert to news of the Muzaffarpur bombing, grew suspicious of the young traveler with the swollen feet and sunken face. Masking his suspicion behind polite conversation, Nandalal subtly tried to extract information. Meanwhile, he secretly dispatched a telegram to Muzaffarpur, tipping off the authorities that he might be sitting beside one of the attackers.

But the spirit of brotherhood still lingered. Mrityunjay, sensing Prafulla’s danger, silently warned him through his expressions. Reading the signal, Prafulla immediately ceased all interaction with Nandalal.

This moment—brief, tense, electric—was one of those fractions of history where revolutions hang by a thread, and yet, even in peril, the loyalty of strangers endured.

As the train made a brief halt at Semuriaghat, Prafulla Chaki stepped down to drink from the sacred waters of the Ganga—perhaps to cool his parched throat, perhaps to ready his spirit for what lay ahead. Irritated by Sub-Inspector Nandalal’s prying questions, he quietly reboarded in a different compartment, hoping to shake off the suspicion trailing him.

But at Mokama Ghat, as he alighted and purchased a fresh inter-class ticket for Howrah, Prafulla sensed it unmistakably—he was being shadowed. The net was closing in. Before he could make another move, a group of armed men, led by Nandalal Bannerjee, Ramdhar Sharma, Shivshankar, Zamir Ahmed, and others, surrounded him with drawn weapons and arrest orders in hand.

But Prafulla Chaki—revolutionary, ascetic, and warrior—would not be taken alive.

He pushed aside the constables, drew his Browning pistol, and fired upon his pursuers in a desperate final stand. Then, with a calm that only true conviction can bring, he turned the pistol upon himself, defiant even in his last breath.

“Shame on you—a Bengali, my countryman—have come to arrest me?”

These were Prafulla’s final words—a searing indictment not just of his captors, but of every soul who failed to rise against tyranny.

He then pulled the trigger. The first bullet pierced his chest, exiting clean through his back. The second tore through his forehead, passing through his prefrontal cortex.

With these two fatal wounds, Prafulla Chaki collapsed instantly—his body broken, but his spirit eternal.

He was not yet twenty.

The British police claimed that Prafulla Chaki shot at the officers and then committed suicide to avoid arrest. This version—widely circulated in colonial reports—sought to depict him as a fanatic who evaded justice.

But doubts soon emerged, not just among fellow revolutionaries but also from forensic observers and independent analysts, who contested the official version. Close examination of police photographs taken of Prafulla's body revealed troubling inconsistencies with the suicide claim. The facts pointed toward a more disturbing possibility: execution disguised as self-inflicted death.

According to modern forensic analysis and eyewitness critique, the following irregularities were noted:

-

The bullet wounds lacked burn or abrasion marks, which typically occur from close-range shots in suicides.

-

Given that Prafulla was right-handed, the trajectory and angle of both wounds—especially the second, through the prefrontal cortex—made it anatomically difficult for him to fire both shots himself.

-

It is highly improbable for a person to shoot a vital area like the chest, and still retain the motor control and strength to accurately fire a second shot into the forehead.

-

No official death certificate signed by a qualified medical professional was ever produced by the authorities.

-

Visible lathi wounds were present on his body, along with blood traces near his mouth and ears, indicating he may have been beaten or tortured before being killed.

These unresolved questions continue to cast a shadow on the British version of events. To the nationalist mind, there remains little doubt: Prafulla Chaki died a martyr—not by his own hand, but by a colonial system terrified of his courage.

Browning pistol 1900 Made

While British records maintained that Prafulla Chaki died by suicide after firing at the police, revolutionary accounts tell a different, far more haunting story. According to some comrades, Prafulla did indeed draw his pistol and fired in resistance—but missed. However, others firmly believe that he was overpowered, brutally beaten into unconsciousness, and then coldly executed with his own weapon.

In this version, the police allegedly staged the scene—firing the pistol once to simulate a struggle, and then using it to deliver two fatal shots to fabricate the illusion of suicide.

Though official history tried to close the chapter quickly, this counter-narrative—passed down in whispers, memoirs, and revolutionary testimony—continues to ignite debate and stir the conscience of a nation that reveres Prafulla Chaki not merely as a rebel, but as a fallen hero betrayed in silence.

Identification and police barbarity

In the aftermath of Prafulla Chaki’s death, the British administration moved swiftly to control the narrative. Two telegrams were sent from Mokama to Muzaffarpur, each a chilling glimpse into how a young martyr's final moments were reduced to official dispatches.

The first telegram, sent at 11:40 AM, stated coldly:

“A Bengali youth, strongly suspected in the bomb outrage, shot himself dead while being arrested.”

Just thirty-two minutes later, a second telegram followed at 12:12 PM, asking:

“Wire immediately what to do with the dead body.”

The Superintendent of Police promptly ordered that Prafulla’s body be brought to Muzaffarpur. That evening, around 5 PM, Superintendent Sohein and Sub-Divisional Officer Bart arrived at the site. A photograph of the body was taken—marking the beginning of the colonial effort to document and close the file on a life that had shaken an empire.

By the next morning, 3 May, at 7:30 AM, the body was transported to Barauni, where it was again photographed. A prior telegraph sent ahead had made the administrative priorities clear:

“Be ready at station with accused and magistrate also civil surgeon – ice and spirits for preservation of body.”

These bureaucratic messages, devoid of emotion, stand in stark contrast to the intensity of sacrifice that Prafulla Chaki embodied. To the British, he was a case to be closed. But to India, he had already become a symbol of unflinching devotion to freedom.

At 3 PM in Muzaffarpur, in the presence of the Magistrate, Police Superintendent, and a gathering of British officials, Khudiram Bose was brought in to identify the body of his fallen comrade. For a moment, he remained silent, his eyes fixed steadily on the lifeless face before him. Then, with quiet certainty, he said:

“Yes, he is — Dinesh Chandra Roy.”

At that time, Khudiram knew him only by his alias—the name they had exchanged in secrecy, never revealing their true identities to one another. It was only during the trial that Khudiram would learn the real name of his comrade: Prafulla Chaki.

But even this final recognition did not satisfy the colonial machinery.

In a shocking display of clinical cruelty, the authorities severed Prafulla Chaki’s head, placed it in spirits for preservation, and handed it over to Deputy Superintendent Bacchu Narayan Lal, who was ordered to carry the decapitated remains to Kolkata for further identification and documentation.

To his fellow revolutionaries, this act was more than desecration—it was an attempt to reduce a martyr to a forensic specimen. But no blade could sever the memory of Prafulla Chaki, which had already become immortal in the hearts of those fighting for India's freedom.

Legacy

Prafulla Chandra Chaki’s martyrdom on 2 May 1908 sent ripples through the revolutionary movement and awakened a generation of Indians to the grim cost of freedom. His sacrifice, borne in silence and fire, was widely mourned, respected, and immortalized in patriotic memory.

Writing in Hitakari (15 June 1908), an editorial offered a solemn reflection:

"His soul has now flown to a higher tribunal where kings and beggars, revolutionists and their rulers stand on the same level and no distinction is made of their respective positions in the dispensation of Justice."

A particularly poignant tribute appeared in the Amrita Bazar Patrika (30 May 1908) from a correspondent in Bogra, Prafulla’s homeland. It offered a heartfelt eulogy to the fallen youth:

That a boy of such a tender age, meek and docile, would come out of such a sleepy hollow as Bogra to join a secret brotherhood was beyond our conception. Born of a quiet, religious family, and the youngest of five children of the late Rajnarayan Chaki of Behar—a village some twenty miles north of Bogra—Prafulla, instead of being 'gay' as his name suggests, was contemplative and devout from early boyhood.

He was rarely seen at play with his comrades but would sit alone for hours in pensive thought. Although of somewhat dark complexion, his broad forehead, pencilled eyebrows, and resolute expression revealed a strong and determined mind.

He was one of the eighty boys who left the Rangpur Zilla School in protest against the oppressive measures of the Fuller Government—an act that helped form the nucleus of national education in Bengal.

Though his career was brief and turbulent, he hailed from a cultured and well-off family. Over a year ago, he had taken formal leave of his mother, uttering words of farewell that were then mysterious to her—but are now tragically clear. Even amidst his perilous mission, he did not forget his mother, writing her two letters from different locations—without postal designation—assuring her that her son was not unhappy or uncomfortable. He informed her that he had embraced the path of brahmacharya, and that he was making progress in both religion and study. He urged her not to worry.

When the tragic news of his death reached the family, it was a shattering blow. But what horrified us most was the news that his severed head had been preserved in spirits for identification. One cannot fathom what our so-called paternal government hoped to achieve with such an unseemly act—especially when photographs had already been taken. Even the enemies' corpses are respected in civilized nations.

This revolting decapitation reminded me of the atrocities during the French Revolution—the ghastly treatment of the Girondist Dufriche-Valazé, whose corpse was paraded with the living to the scaffold. I close this letter with the final words of brave Prafulla, as reported at the brink of his martyrdom:

"You—a Bengali, my countryman—have come to arrest me?"

In sharp contrast to the reverence with which Prafulla was remembered by his countrymen, the British administration rewarded betrayal. Nandalal Banerjee, the sub-inspector who assisted in capturing Prafulla, was awarded ₹1,000 at a durbar in Muzaffarpur on 10 May 1908. Yet, within the revolutionary underground, he was forever branded a traitor.

That condemnation was not merely symbolic. On 9 November 1908, in Serpentine Lane, Kolkata, Nandalal Banerjee was assassinated by Srish Pal, aided by Ranen Ganguly, both revolutionaries affiliated with the Mukti Sangha and Atmonnati Samiti. They vanished into the shadows, their identities whispered but never confirmed—turning justice into myth and memory into fire.

Commemoration and historical memory

Though a key figure in India’s early revolutionary movement, Prafulla Chaki remains a relatively lesser-known martyr when compared to his comrade Khudiram Bose, who was captured alive and executed on 11 August 1908. Khudiram’s dramatic trial and youthful defiance drew widespread public attention, while Prafulla's death, shrouded in controversy, has long been suspected by many as an extrajudicial killing—a suspicion that has never been conclusively resolved.

Despite this, efforts have been made over the years to honor his sacrifice:

-

Busts of Prafulla Chaki have been installed in both Muzaffarpur and Kolkata, paying tribute to his fearless spirit.

-

In 2010, the Government of India issued a commemorative postage stamp bearing his name, symbolically restoring him to the national memory.

-

The Biplabi Prafulla Chaki Memorial Trust, based in Shibrampur, Kolkata, actively works to preserve his legacy and spread awareness of his contributions to India’s freedom struggle.

Yet, Prafulla Chaki remains an unsung hero, overshadowed in mainstream narratives but revered in the hearts of those who understand the sacrifices that shaped India's path to independence. His life, cut short at just 19, is a reminder that the spirit of revolution often begins in silence, in contemplation, and in unflinching courage.

Today, his family continues to uphold his legacy. His descendants live in Uttar Dinajpur and Dakshin Dinajpur districts of West Bengal. Subrata Chaki, great-grandson of Prafulla’s elder brother Pratap Chandra Chaki, serves as the president of the Memorial Trust, residing in Kolkata and striving to ensure that Prafulla’s story is neither forgotten nor diminished.

Bibliography

- Hemanta Chaki, Agnijuger Pratham Shahid Prafulla Chaki, Calcutta 1952

- Indian Unrest by Valentine Chirol, 1910

- Khudiram Bose: Revolutionary Extraordinaire by Hitendra Patel, 2008

- Abishmaraniya by Ganganarayan Chandra [full citation needed]

- Ke Khudiram ? by Arindam Bhowmick, 2017

- THE STORY OF INDIAN REVOLUTION, by Arun Chandra Guha, Calcutta 1965

- Shailesh Dey, Mrityur Cheye Baro, Calcutta 1971

- Kalicharan Ghosh, Roll of Honour, Calcutta, 1960

- Mul Nathi Theke Khudiram O Prafulla Chaki by Chinmoy Chowdhury, 1959

- Prithwindra Mukherjee, Bagh Jatin, Dey's publishing, 2019

- Ramesh Chandra Majumdar, History of the Freedom Movement in India, III, Calcutta 1963

- Hemendranath Dasgupta, Bharater Biplab Kahini, I, Calcutta, 1948

References

- ↑

Chaki, Hemanta (1952). Agnijuger Pratham Shahid Prafulla Chaki.

- ↑

"Calcutta High Court Khudiram Bose vs Emperor on 13 July, 1908". Indian Kanoon. Retrieved 5 June 2018.

- ↑

Arun Chandra Guha (1971). First spark of revolution: the early phase of India's struggle for independence, 1900-1920. Orient Longman. p. 131. OCLC 254043308.

Khudiram was suspected and arrested there [at Waini station] ... Khudiram was tried ... was sentenced to death and hanged in the Muzaffarpur jail ... on 19 August 1908.

- ↑

Rama Hari Shankar (1996). Gandhi's encounter with the Indian revolutionaries. Siddharth Publications. p. 48. ISBN 978-81-7220-079-4.

- ↑

Lakshiminiwas Jhunjhunwala (2015). Panorama. Ocean Books Pvt. Limited. p. 149. ISBN 978-81-8430-312-4.

- ↑

Mahatma Gandhi (1962). Collected works. Publications Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Govt. of India. p. 223.

- ↑

Bhaskar Chandra Das; G. P. Mishra (1978). Gandhi in to-day's India. Ashish. p. 51. ISBN 9788170240464. OCLC 461855455.

- ↑

"The story of our independence: Six years of jail for Tilak". Hindustan Times. 8 August 2015. Retrieved 11 August 2018.

- 1 2

Chakraborty, Praphullakumar (1955). Pharasi Biplab.

- ↑

"Chaki, Prafulla". Banglapedia. Retrieved 11 January 2020.

- ↑

"Prafulla Chandra Chaki". istampgallery.com. 5 December 2014. Retrieved 11 January 2020.

- 1 2

Biplab Ghosh (22 October 2017). Ichapur Barta Edited By Biplab Ghosh.

- ↑

Thakur, Basab (1935). Dwitiyo Biplab.

- ↑

Bagchi, Kironendu (1980). Banhi Biplab.

- ↑

Rajnikant Puranik (2017). Revealing Facts about India's Freedom Struggle by Rajnikant Puranik.

- 1 2 3 4

Ritu Chaturvedi (2007). Bihar Through the Ages. Sarup & Sons. p. 340. ISBN 978-81-7625-798-5.

- ↑

Datta, Kanailal (1959). Mahajibaner Punyaloke.

- 1 2

"DYNAMITE OUTRAGE". Daily Telegraph. 10 December 1907. Retrieved 11 July 2025.

- ↑

"Attempted Train Wrecking". National Advocate. 10 December 1907. Retrieved 11 July 2025.

- ↑

"LATEST CABLEGRAMS". Manning River Times and Advocate for the Northern Coast Districts of New South Wales. 11 December 1907. Retrieved 11 July 2025.

- ↑

Shil, Kanailal (1951). Mukti-tirtha Ed. 4th.

- ↑

Ghosh, Manoranjan (1950). Chattogram Biplab Ed. 2nd.

- ↑

"ATTEMPTED TRAIN WRECKING". Wagga Wagga Express. 10 December 1907. Retrieved 11 July 2025.

- ↑

- ↑

"DYNAMITERS IN INDIA". Barrier Miner. 10 December 1907. Retrieved 11 July 2025.

- ↑

Arabinda Mandire অরবিন্দ মন্দিরে. Prabartak Publishing House, Chandannagar. 1922.

- 1 2

"OUTRAGE IN INDIA". Age. 10 December 1907. Retrieved 11 July 2025.

- ↑

"SIR ANDREW FRASER'S LUCKY ESCAPE. The Straits Budget, 12 November 1908, Page 14". eresources.nlb.gov.sg.

- ↑

"SIR ANDREW FRASER". Observer. 12 December 1908. Retrieved 11 July 2025.

- ↑

"ATTEMPTED OUTRAGE". Zeehan and Dundas Herald. 10 December 1907. Retrieved 11 July 2025.

- ↑

"ATTEMPTED DERAILMENT". Examiner. 10 December 1907. Retrieved 11 July 2025.

- ↑

Hitendra Patel (2008). Khudiram Bose: Revolutionary Extraordinaire. Publications Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting. p. 43. ISBN 978-81-230-1539-2.

- ↑

"INDIAN TRAIN-WRECKERS". Sydney Morning Herald. 13 April 1908. Retrieved 11 July 2025.

- ↑

"INDIA". North West Post. 10 December 1907. Retrieved 11 July 2025.

- ↑

Sarkar, H. k (1923). Revolutionaries Of Bengal.

- ↑

Heehs, Peter (1993). The bomb in Bengal : the rise of revolutionary terrorism in India, 1900-1910. Internet Archive. Delhi ; New York : Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-563350-4.

- ↑

Lahiri, Somnath Tr (1961). Bigyane Biplab.

- ↑

Sarkar, satishchandra (1931). Biplab Pathe Spain.

- ↑

Roy, motilal (1923). Biplabi Shahid Kanailal Ed.1st.

- ↑

Basu, Jyoti Prosad (1946). Biplabi Kanailal Ed. 1st.

- ↑

Majumdar, Satyendranarayan (1971). Aamar Biplab-jigyasa Parbo.1(1927-1985).

- ↑

Kanungo, Hemchandra (1929). Banglay Biplab Prachesta Ed. 1st (in other). NA.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ↑

Bandyopadhyay, Basanta Kumar (1927). Jiban Brittanta.

- ↑

Ray Dalia (1909). The Bengal Revolutionaries And Freedom Movement.

- ↑

Jogeshananda Saraswati (1950). Gita Katha Ed. 1st.

- ↑

GUHA, ARUN CHANDRA (1972). THE STORY OF INDIAN REVOLUTION. PRAJNANANDA JANA SEVA SANGHA, CALCUTTA.

- ↑

Sarkar, Tanika (2014). Rebels, wives, saints : designing selves and nations in colonial times. Internet Archive. Ranikhet : Permanent Black. ISBN 978-81-7824-396-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: publisher location (link) - ↑

Not Available (1920). Jug-barta.

- ↑

SAREEN, TILAK RAJ (1979). INDIAN REVOLUTIONARY MOVEMENT ABROAD(1905-1921). STERLING , NEW DELHI.

- ↑

Ray, Dinendrakumar (1923). Arabinda-prasanga.

- ↑

Dasgupta, Sri Hemendranath (1946). Bharater Biplab Kahini Vol. 1.

- ↑

Dey, Purnachandra (1945). Mrityunjayee Kanailal.

- ↑

Remembering our leaders. Children's Book Trust. 1989. ISBN 978-81-7011-545-8.

- ↑

Ray, Motilal (1957). Amar Dekha Biplob O Biplobi.

- ↑

- ↑

"The Muzaffarpur Outrage. Straits Echo, 18 May 1908, Page 9". eresources.nlb.gov.sg.

- ↑

Chandra, Ganganarayan (1966). Abishmaraniya Vol. 2.

- ↑

- ↑

Ray, Motilal (1880). Bijaychandi Gitabhinay বিজয় চন্ডী গীতাভিনয়.

- ↑

Chandra, Ganganarayan (1964). Abismaraniya Vol. 1.

- ↑

Ray, Bhupendrakishore Rakshit (1960). Bharate Shashastra Biplab.

- ↑

"ANARCHISM IN INDIA. Pinang Gazette and Straits Chronicle, 20 May 1908, Page 3". eresources.nlb.gov.sg.

- ↑

Ray, Motilal (1929). Aatmasamarpan Jog আত্মসমর্পন যোগ. Prabartak Publishing House, Kolkata.

- ↑

Arun Chandra Guha (1971). First spark of revolution: the early phase of India's struggle for independence, 1900-1920. Orient Longman. p. 131. OCLC 254043308.

A Bengali police officer, Nandalal Banerji was also travelling in the same compartment ... Nandalal suspected Prafulla and tried to arrest him. But Prafulla was quite alert; he put his revolver under his own chin and pulled the trigger ... This happened on the Mokama station platform on 2nd May, 1908.

- ↑

SUR, SHRISH CHANDRA (1938). JAGARAN জাগরণ (in other). SATYENDRABNATH SUR, CHANDANNAGAR.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ↑

Rakshit, Bhupendrakishor (1960). Bharater Sashastra-biplab.

- ↑

Guha, Nalinikishor (1954). Banglay Biplabbad.

- ↑

GHOSH, KALI CHARAN (1960). THE ROLL OF HONOUR. VIDYA BHARATI,CALCUTTA.

- ↑

- ↑

Jug-Barta যুগবার্তা. Prabartak Publishing House, Chandannagar. 1920.

- ↑

"OUTRAGE IN CALCUTTA. The Straits Times, 18 November 1908, Page 8". eresources.nlb.gov.sg.

- ↑

RAY, MOTILAL (1957). AMAR DEKHA BIPLOB O BIPLOBI আমার দেখা বিপ্লব ও বিপ্লবী (in other). RADHARAMAN CHOWDHURY, KOLKATA.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ↑

Bose, Subhas Chandra. Subhas-rachanavali Vol. 2.

- ↑

"Untitled The Straits Times, 10 September 1908, Page 6". eresources.nlb.gov.sg.

- ↑

Subodh ch. Sengupta & Anjali Basu, Vol - I (2002). Sansad Bangali Charitavidhan (Bengali). Kolkata: Sahitya Sansad. p. 541. ISBN 978-81-85626-65-9.

.png)

Comments

Post a Comment